Petrochemical Companies are Pushing Chemical Recycling

They call it “advanced recycling,” but it’s neither advanced nor recycling

Although “chemical recycling”—and other terms like “advanced recycling” and “molecular recycling”—are promoted by the plastics and petrochemical industries as a solution to the plastic waste crisis, they are not true recycling processes, nor are they actual solutions to the plastic waste crisis. Chemical recycling plants in the United States are currently handling less than 1% of the plastic waste generated in this country and it’s not new - they have been trying this technology for decades.

The term “chemical recycling” has no legal definition but refers to a diverse set of projects that subject plastic waste to a combination of high heat, pressure, and/or chemicals. While conventional mechanical recycling preserves the polymer structure of plastic waste while processing it into new plastic products, most chemical recycling technologies break the polymer structure during processing. These technologies are known by many names, including advanced recycling, molecular recycling, gasification, pyrolysis, waste-to-fuel, solvolysis, methanolysis, and thermal demanufacturing.

Chemical recycling facilities produce minimal recycled plastic that can actually displace virgin plastic made from fossil fuels. For example, the Freepoint chemical recycling facility located in Hebron, Ohio claims that for every 170 million pounds of waste plastic it processes through pyrolysis, 26 million pounds of “new plastic will be created. That means that out of every six and a half pounds of waste plastic processed, just one pound will become new plastic while about five and a half pounds will end up as by-products that will have to be landfilled, burned as hazardous waste, or released as air pollution.

Most Facilities Turn Plastic Waste into Small Amounts of Fossil Fuels

The vast majority of plastics subjected to chemical recycling processes are used as fuel, not as feedstock for new plastic products. Petrochemical companies have announced that they will have 2 million tons of global chemical recycling capacity by 2027, with only 20% of this is slated to become new plastic.

The most common chemical recycling process used in the U.S. is pyrolysis, which uses high heat and pressure in low-oxygen conditions to convert waste plastic into fuels and byproducts. Non-combustible gas (or “syngas”) produced in these plants is usually burned directly at the facility to power the process, while liquid fuel produced (“pyoil”) is typically sold as fuel to be burned, with only small quantities being fed back into cracker plants to be made into plastic precursor chemicals. Pyrolysis has therefore been excluded from the definition of recycling by government bodies:

United States (federal): The US EPA currently regulates pyrolysis and gasification as incinerators, included in Other Solid Waste Incineration Standards (OSWI) under Section 129 of the Clean Air Act although the Trump Administration is working to change that designation.

European Union: EU Directive 2008/98/EC on waste defines recycling as "any recovery operation by which waste materials are reprocessed into products, materials, or substances…but does not include energy recovery and the reprocessing into materials that are to be used as fuels.” Since pyrolysis predominantly produces fuels, it does not meet this definition.

Poor Track Record

Chemical recycling is not a new idea; companies have been trying for decades to make it work. Both the complex chemical makeup of plastics and the challenges of securing a clean, sorted, homogenous source of waste plastics mean that chemical recycling technologies simply do not work at scale. As a result, chemical recycling plants across the U.S. face delays, barriers, and cost overruns – not to mention their release of hazardous air pollutants, or the fire dangers posed by stockpiling waste plastic on site.

A Drop in the Bucket: Only 1% of Plastic Waste Actually Handled

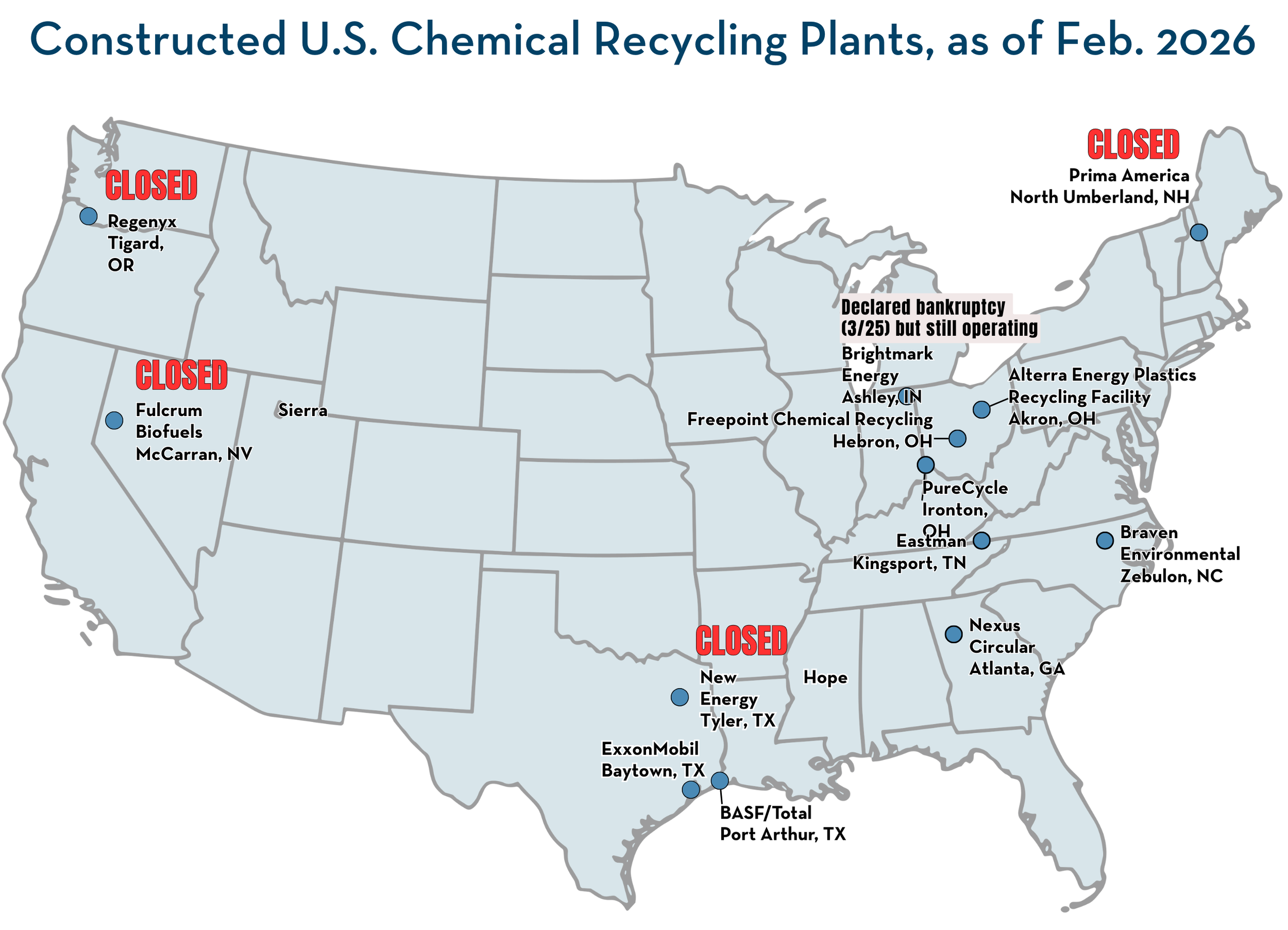

In October 2023, Beyond Plastics and the International Pollution Elimination Network (IPEN) published the report “Chemical Recycling: A Dangerous Deception.” At the time of publication, there were only 11 constructed facilities in the U.S.: eight used pyrolysis, two gasification, one solvolysis, and one solvent-based purification (the total equals 12 because Eastman has two processes). Together, these facilities had a maximum processing capacity of about 460,000 tons per year—or only 1.3% of the amount of plastic waste generated in the U.S.

However, most of the plants were not operating at full capacity, and three of them closed in 2024 due to a combination of financial challenges and technical difficulties (Regenyx in Oregon, Prima in New Hampshire, and Fulcrum in Nevada). New Hope in Texas also shut its doors, although it has reportedly done so to make way for a larger facility. In addition, Brightmark in Indiana—struggling at only 5% of rated capacity—declared bankruptcy and was bought at auction by its parent company.

According to Oil & Gas Watch, there are currently 41 plants either proposed or under construction in 14 states, with notable concentrations in Ohio, Louisiana, and Texas. Many of these facilities will not be built, in part because construction costs can be as much as half a billion dollars per plant and it is challenging to raise investment capital, even with public subsidies.

A Heavy Burden on Environmental Justice Communities

A majority of these facilities are located in environmental justice communities: places where the percentage of low-income households or people of color are higher than the national or state averages.

A Toxic Soup of Chemicals

More than 16,000 chemicals are used to make plastics. More than a quarter of these chemicals (4,219) are known to be harmful to human health and/or the environment: they are carcinogenic, mutagenic, toxic to reproductive and endocrine systems, or toxic to aquatic organisms. Even more of these chemicals (10,726) have not yet been studied for safety. During chemical recycling, these chemicals may be released, can become reactive, and can pollute the surrounding environment:

Hazardous wastes produced by chemical recycling include polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), dioxins and furans, persistent organic pollutants (POPs), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and heavy metals.

Two of the operating U.S. plants are classified by the Environmental Protection Agency as large quantity generators of hazardous waste (Alterra and Braven), while one is classified as a very small quantity generator (PureCycle).

The toxic chemical additives used in plastic also raise concerns about the chemical safety of consumer products that are made from recycled plastic. During chemical recycling, chemical additives and contaminants from different plastics can accumulate, and additional hazardous substances may form as a result of heat, pressure, and mechanical stress. Many recycled plastics are unsuitable for food-grade uses and studies have reported potentially harmful chemicals in products made from recycled plastics, including bottles and toys, and food packaging materials.

Climate Impacts

Carbon emissions from chemical recycling will contribute to climate change. A recent study found that greenhouse gas emissions from making plastic polymers from the pyrolysis or gasification of plastic waste were 10 to 100 times greater than emissions from making plastic polymers from virgin inputs (such as ethane from fracking).

MORE RESOURCES

ISSUE BRIEF: More Recycling Lies: What the Plastics Industry Isn't Telling You About "Chemical Recycling" | NRDC | March 2025

REPORT: Chemical Recycling: A False Promise for the Ohio River Valley | Ohio River Valley Institute | July 2024

MEMO: The Fraud of Advanced Recycling | Center for Climate Integrity | April 2024

REPORT: Chemical Recycling: A Dangerous Deception | Beyond Plastics and International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN) | October 2023

ISSUE BRIEF: Recycling Lies: “Chemical Recycling” of Plastic Is Just Greenwashing Incineration | NRDC | February 2022

FACT SHEET: “Chemical Recycling” Is Not Recycling: The Plastic Industry Is Greenwashing Incineration | NRDC | September 2022

FACT SHEET: El “Reciclaje Químico” No Es Reciclaje: La Industria Del Plástico Hace Un “Lavado Verde” (Greenwashing) Acerca De La Incineración | NRDC | Septiembre 2022

Updated February 2026